C2 Smackdown - Empire vs Mythic

I found evaluating platforms like this to be a great way to familiarize myself with them quickly, so I’ve opted to do this test again. The last time I compared C2’s, it was Havoc vs Sliver, and Sliver came out on top because they simply had more resources that they could dedicate to development and expansion. But Havoc was impressive for what it was, a Cobalt Strike lookalike that was developed by one primary person. It showed a lot of promise and I’m sure the developer will flesh this out into a fantastic platform. However, for this test, Empire and Mythic are both backed by companies with a large staff pool and have resources to spend on development, so it should be a much fairer comparison. There will be four categories that the platforms will be tested on, (1) what’s the GUI like, (2) what options are there for generating implants, (3) how do you interact with agents, and (4) if there is an option for an after engagement summary. These goals are slightly adjusted from the prior test in order to represent what I think are more important features people evaluating which product fits their needs will want to see. For each platform, I’ve established a persistent implant and then run some common tools like SeatBelt and Rubeus to see how easily these are executed. I’ve also taken a look at that backend code that is running so as to point out neat tricks or shortcuts that the development teams have taken, for better or worse.

Mythic

Mythic is partially maintained by SpecterOps, a cybersecurity company that is also known for development of BloodHound. A fun detail linking this all neatly together, harmj0y developed both Empire and BloodHound. Mythic states their main goals are a platform that allows plug and play architecture where modifications can happen on the fly and contains robust reporting for breaking down and attributing each command to each operator. They state the following about their logging which sums it up nicely.

From the very beginning of creating a payload, Mythic tracks the specific command and control profile parameters used, the commands loaded into the payload and their versions, who created it, when, and why. All of this is used to provide a more coherent operational view when a new callback checks in. Simple questions such as “which payload triggered this callback”, “who issued this task”, and even “why is there a new callback” now all have contextual data to give answers. From here, operators can start automatically tracking their footprints in the network for operational security (OpSec) concerns and to help with deconflictions.

Aside from the robust reporting, Mythic also has a lot of nice-to-haves. One of these is a credential vault for storing credentials, keys, and miscellaneous other things that you wouldn’t want to be exposed. The credential vault uses a three way combination of Hasura, GraphQL, and Postgres to store, process, and display information and the database is secured through a randomly generated password that you can see in the .env file of your Mythic installation.

What is the GUI like

The Mythic GUI is intuitive to figure out with options to configure profiles, payloads, examine artifacts and findings, and export reports. To determine the admin password, you use a command line argument and it prints it out since each install has a randomly generated one. Generating new user accounts is simple enough through a provided menu and you can delegate admin access with just a button for each account.

Implant generation options

Mythic takes a unique and interesting approach to generating implants. It comes with no native implant or listener options so instead you have to download some from a precompiled list on GitHub. Thankfully there are many implant options from Apfell to Merlin. This allows a lot of flexibility with what implants you want to use. The same is true for listeners, you need to download each one you want to use. I think this is a knock against the platform because they themselves don’t ensure that a base line will always be available and developed alongside the backend.

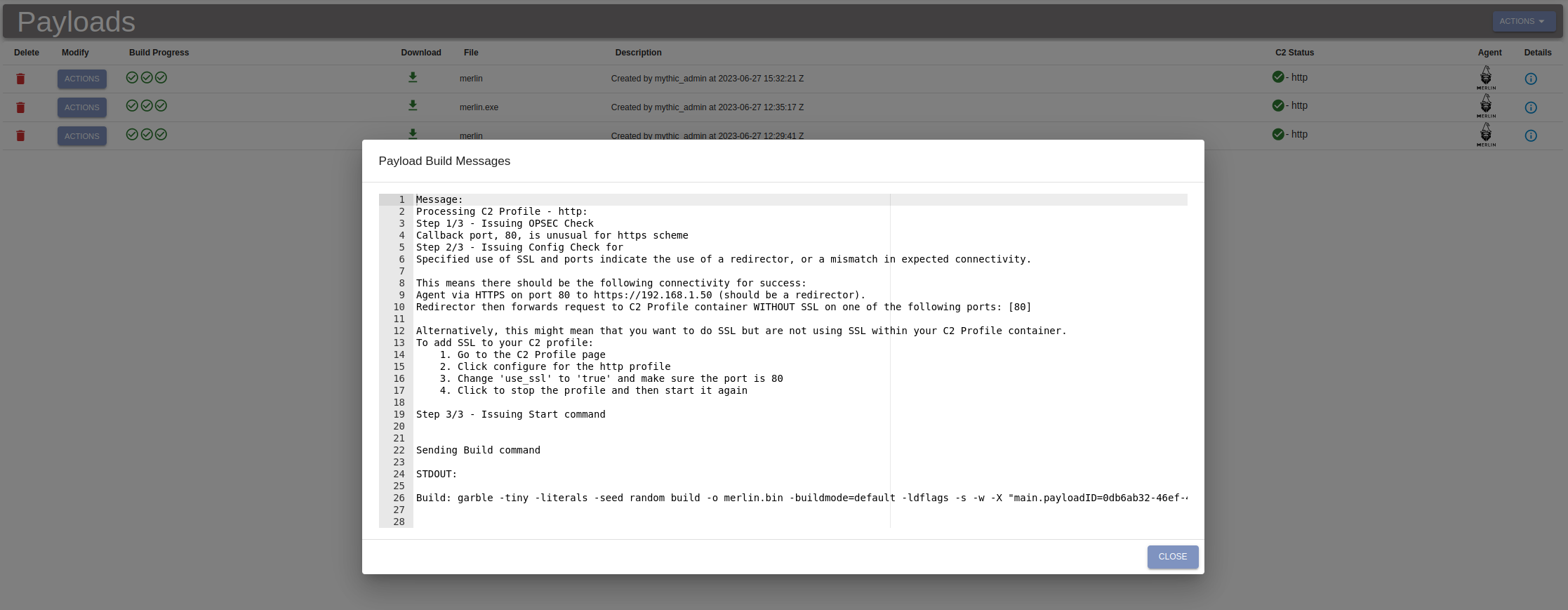

For the purposes of this test, I chose to use an HTTPS listener because Merlin requires HTTPS to function with the HTTP2 protocol and the Merlin agent, just because I have a Merlin sticker on my water bottle and it’s the coolest looking design.

A small annoyance is that compiling implants takes my VM a couple minutes. What’s a bigger annoyance, though, is that the listener profile defaults to HTTPS when creating a new listener but the listener profile defaults to SSL=false in the global configuration setting. So after generating an implant without issue, you will notice that they aren’t connecting back to the C2. You then go to the implant page and look at the details for the build, and there it tells you that you compiled for HTTP(S) but you have SSL set to false so this is something you need to fix.

But why not just default to SSL being true in the HTTP profile or default to not using HTTP(S) in the implant?

Apart from the above hiccup, there was a nice variety of OS and architecture options with Merlin and you could compile to target a number of systems that you are likely to see on an engagement. There were four Nix flavors ranging from Solaris to Linux as well as Mac and Windows, meaning you should have no trouble with compiling for enterprise environments.

Interacting with agents

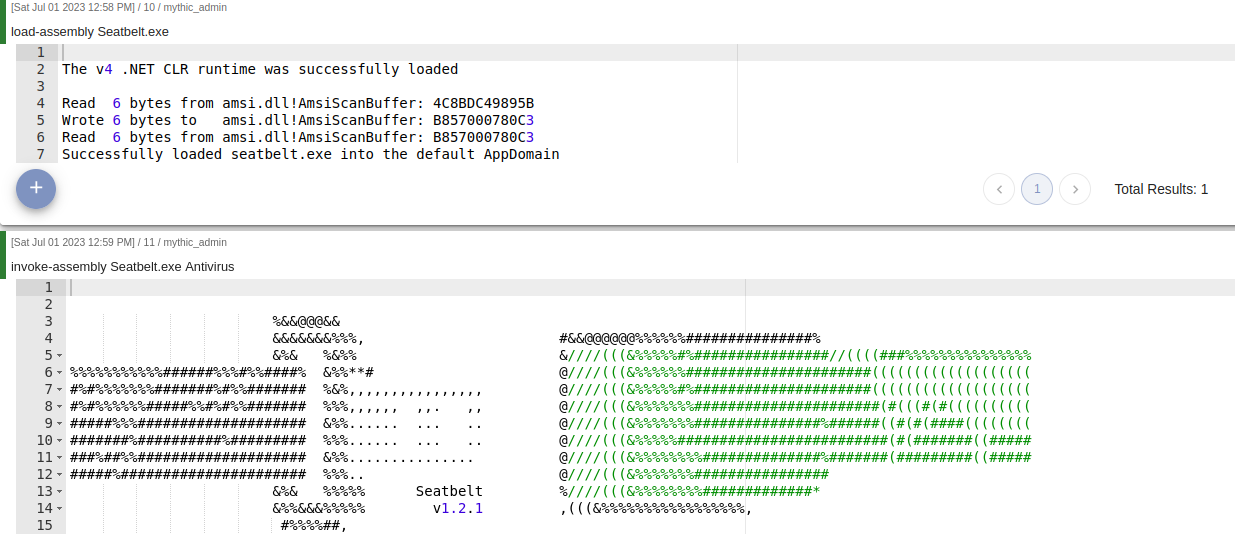

A feature I learned to love very quickly were the load/invoke-assembly commands. These allow you to load a .NET assembly into the implants process and then execute it as much as you wanted with any arguments without having to resend the assembly to the implant, which keeps your network footprint relatively low. For example with SeatBelt, I could just load it into the process space and then execute the command with an array of arguments.

This is a huge quality of life feature. The same can be done for Rubeus and any other .NET compiled executable. I was curious if this would work with any PIC executable, but the feature specifically uses AppDomains which are a .NET specific environment to execute applications. The purpose behind AppDomains is that if they become unstable or threaten to otherwise crash, they can be unloaded without affecting the core process. This is important in the context of an implant as sometimes tools encounter unknown issues and panic, and if that were to affect the implant stability, it would be annoying having to achieve execution repeatedly. For those familiar with Cobalt Strikes sacrificial process - this is the same principle.

Speaking of sacrificial processes, you can also that with create-process. From the description, this uses process hollowing to create a new child process and then collects stdout from it with anonymous pipes.

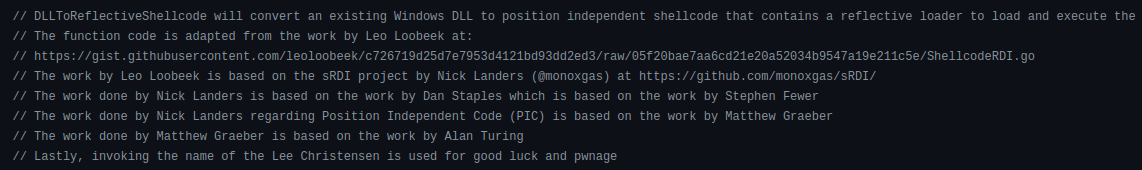

Merlin also contains an option for shellcode reflective DLL injection which attempts to convert a DLL into shellcode. The code in Merlin has a nice chain of attribution

What will perhaps be the second most useful command is token which allows you to steal another processes security token, among other useful args like getting the current context of your security token. A little background to security tokens is that in the context of Windows, for each and every process created there is a security token delegated to it. This allows the security boundary to only have to check the token privileges as opposed to reauthenticating the users privileges each time the object is called. Merlins documentation identifies that it uses the DuplicateTokenEx Windows function in order to accomplish this. It is important to note that this could be regarded by some SIEMs as a suspicious API call and cause an alert to fire. But this is a preferable trade off for privilege escalation as opposed to dumping LSASS.

Post operation reporting

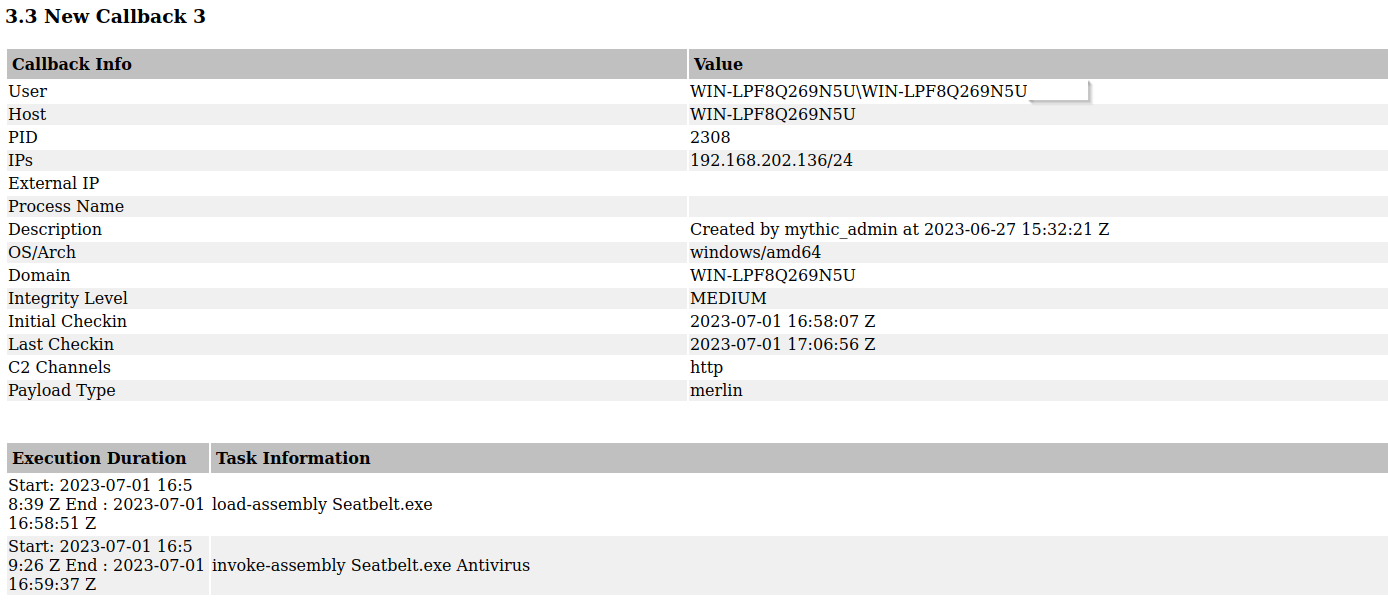

A good quality of life feature that I liked is that you could name your operation, giving some personal flare and pizzazz to the exercise and allowing for easy organization. Generating reports is also very easy and allows you to see a breakdown of commands issued by each operator. For example, using the earlier SeatBelt command, we can see when it was issued and who by.

Empire

A bit of background. PowerShell Empire (here after just referred to as Empire) was developed as a response to nation-state attackers using native PowerShell to launch their payloads in a fileless manner. At the time, since PowerShell was trusted by major vendors, EDR did not stop or detect PowerShell based attacks. Due to this, several members of the infosec community stepped up to create a post-exploitation kit that could demonstrate the severity of this threat. Then around 2020, the project shut down after the maintainers determined they had reached their goal of making vendors aware of this threat. Empire remained defunct until BC Security forked it and took over active development. Now, they make regular contributions to the project and have releases for big updates.

BC Security’s biggest contribution has definitely been the Starkiller GUI for Empire. However, this leads into an issue: Where should I draw the line of saying that they built Empire? I will try my best to point out different contributions by each team because they merit individual consideration. For example, the original Empire team didn’t make very robust documentation and this would be a great place for a development team to make big strides. It would also make sense for a team taking over a new project to document all the functions in the app. Unfortunately, BC Security didn’t do that; the wiki is lacking a lot of information on how to navigate the Starkiller UI and I had to go to the C2 Matrix to even find the default username/password.

The original Empire team did a fantastic job, obviously, with their PowerShell functions. At the time it was a unique framework and to see something like this released to the public for free, it made a big impact. This is evident by the quick adoption from nation-state actors as recognized by SANS and Microsoft. And this quick adoption prompted EDR vendors to step up their detection engines seriously in order to deal with what was now a pervasive threat.

The new Empire team has also made a series of important updates to the platform. One of the first blog posts that BC Security did about Empire had to do with updating the CLI to interact with Empire through an API allowing multi operator interaction. That’s massive. Another huge update they did was to include the Python Prompt Toolkit. This allowed intelligent predicted response suggestions to what you are typing in real time. This isn’t even mentioning the Starkiller GUI that works on top of Empire.

What is the GUI like

The Starkiller UI is interesting. It’s still in its early infancy and there are many rough spots I’ve found. There are your typical pages for listing agents and creating new listeners, but it’s not intuitive to figure each menu out. For example, generating new implants is iffy. Instead of there being a page dedicated to it, you have to go through the stagers page. This seems counter intuitive and there’s no obvious indication saying that you generate your implants here. On top of that, the error messages don’t tell you anything. It would be working fine and then I would try to do something the app didn’t like and I get a 500 server error. But that’s all I’m told. I’m not told why the operation failed. I think detaching the stager options from the implant generation would make the menus feel more intuitive.

Implant generation options

When I first opened Empire I was a little surprised to see all the implant options. There are a staggering number ranging from Windows command exec options to generating a Nix WAR file. Then I looked further and thought to myself this looked a lot like Metasploit. And then looked even further at BC Security’s GitHub contributions and found that in a number of the Windows generators they were directly calling MSFVenom for payload generation options. It looks as though to add new features, instead of sticking with the theme of PowerShell, they implemented calls to Metasploit through the CLI and grabbed the output. I don’t like this approach because I think it detracts from the theme of the projects’ origins since MSFVenom generated executables aren’t “fileless.”

Sliver did this too to an extent and I want to recognize how their approach differs from Empire. Sliver implements MSFVenom by working alongside it, using it to compliment some of their payloads and taking advantage of the encoder options. Sliver has also implemented in Go a technique for injecting Metasploit payloads into a remote process. It builds off of MSF as opposed to just calling it.

BC Security does have a stated reason for this, however, which is worth a bit of discussion. The team recognized the smallest they could make an Empire payload was in the thousands of kilobytes. But by using MSFVenom for reverse shell stagers, they were able to reduce the file size to in the tens of kilobytes. This allows the payload to have a higher success chance in certain cases of buffer overflow attacks where the small buffer size does limit the attack surface. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me because the staged options output executables for Windows instead of bytecode, and I don’t believe these executables are position independant code. But I may be wrong here!

Empire does do a great job of providing a number of options for attacking platforms other than Windows. There’s eleven OSX attack types to choose from, each using very different techniques to accomplish execution. I didn’t get a chance to test these but I wonder how likely they are to work since they still closely resemble what the original Empire authors had crafted and Apple does not slack on patching security oversights I’ve found.

Interacting with agents

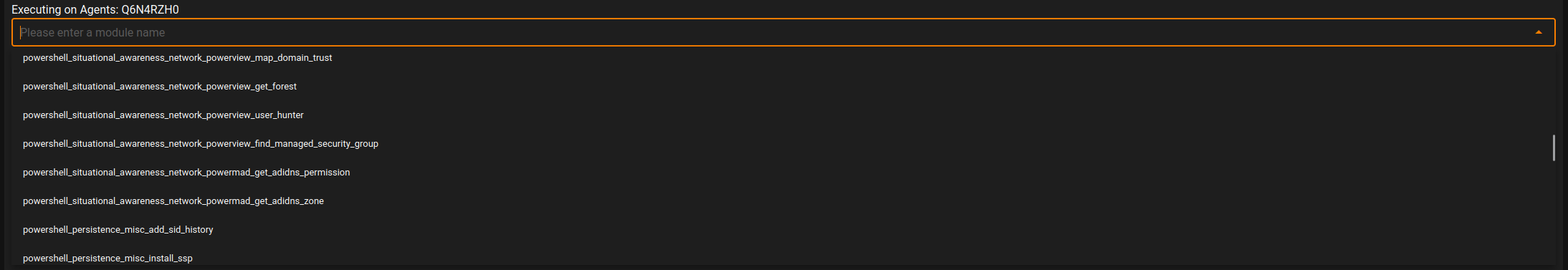

This is where I started to like Empire, and Starkiller, a lot more. There were some initial hiccups, but both the original developers and BC Security did a fantastic job with giving operators a full arsenal of tools. There is a silly amount of commands that you can run on agents. This is great because options! But also it can be bad and overwhelming because it is literally hundreds of possible commands ranging from PowerShell to Python to CSharp. If there were obvious categories that they could be grouped into and names given other than what reads like an internal notation, it would be much more legible. But as it stands, this makes the GUI feel crowded. Here’s a snippet halfway down the command list of what the options look like.

Despite this, a feature I immediately liked was the ability to inject BOF’s similarly to Sliver. This greatly expands post compromise potential and feels very in the spirit of what Empire was initially about - fileless functionality. This was also coded in PowerShell and utilizes a function created by citronneur to load and map a BOF file into memory and then execute it in a manner defined by the user.

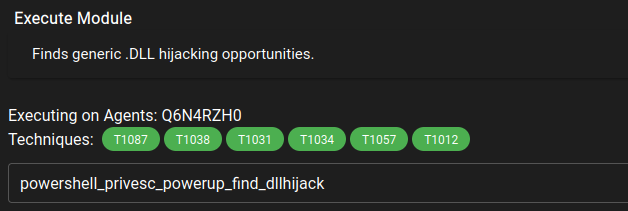

A really cool feature in Starkiller is how they map commands to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This gives hints to what it could look like when reporting is released to the public since command mapping and attribution is a big part.

Another interesting feature revealed itself when I was looking further at their Python scripts and one in particular caught my eye. This is the linuxprivchecker.py file. This is a pretty simple implementation that utilizes the os.popen Python function to execute a series of commands that gets the kernel version, network interfaces, cron jobs, and other system info. Looking at the code, it’s definitely not OPSec safe, and the Starkiller UI makes sure to tell you. This is a nice touch to help remind operators when commands will definitely reveal them.

I would love to see some contributions to the credential module page to include token stealing through a .NET implementation of DuplicateTokenEx similar to how Merlin did this, as relying on LSASS dumping through Mimikatz is regarded as an old tactic now.

Post operation reporting

There is an option for reporting but it is locked behind the sponsored version as of the time of writing.

When might you want one or the other?

Mythic wins out on their reporting feature and robustness of the API. However, you will probably want an experienced developer on the team that can work with their API so you’re not reliant on 3rd parties that could drop support for their profiles or agents on a whim. That being said, Empire in its current form is not nearly as feature rich or advanced as Mythic. It lacks core commands that Merlin provided and the Starkiller GUI is currently a lot more complicated than Mythic. I think Mythics post engagement reporting should be a core feature that more platforms aspire to as it provides a great tool for both in the moment deconfliction and a starting point for discussion with stakeholders afterwards. It allows teams to point out which commands were not caught or otherwise flew under the radar.

I am not a fan of Empire in its current form and I think that came across in the section on it. If you read that section and thought I was a total moron, fair enough! I may just not “get” Empire like others have, and I know nation-state actors continue to abuse it to this day. But they’re not using off the shelf copies of Empire that match the latest release. The same is true of Mythic. On Shodan, there are less than fifty instances of Mythic publicly exposed that are running the default configuration. Forking a project as well known as Empire in order to take over active development is a big task. It would be big for anyone. You have a whole code base to familiarize your team with, interactions between different components to understand, and you have to develop community interaction to understand friction points within the software. And BC Security has definitely done this. They run workshops, they offer trainings, they have an active blog on their website which I’m a big fan of. I almost think it would have been easier to start from scratch with making a new C2 as opposed to trying to make Empire work in the manner they want. But I applaud their efforts to keep Empire current and make it an appealing platform for teams looking for open-source solutions.