The evolution of evasion

Evasion is a very interesting topic. When I say evasion, I’m referring to both evading prying eyes from analysts and avoiding their attention, as well as evading AV and EDR. We can see how espionage operations in 2000 led to advancements in EDR and OS mitigations today in 2023. The Equation Group is fascinating to study in this area because for so long their operations went unattributed. And this can be directly tied to how well they tailored their target list and worked to keep themselves from being discovered. Thanks to the Shadow Brokers and Kaspersky, we are able to now get a deep insight into their specific methodology and techniques used in one stage of their operational development. Kaspersky also provided a lot of great analysis and documentation in the year leading up to the public release of the toolsets. After analyzing some of Equation Groups leaked tools, I’ll also touch on some modern developments in evasion. The modern land scape is a lot different than even just a couple years ago - go figure.

EQUATIONDRUG

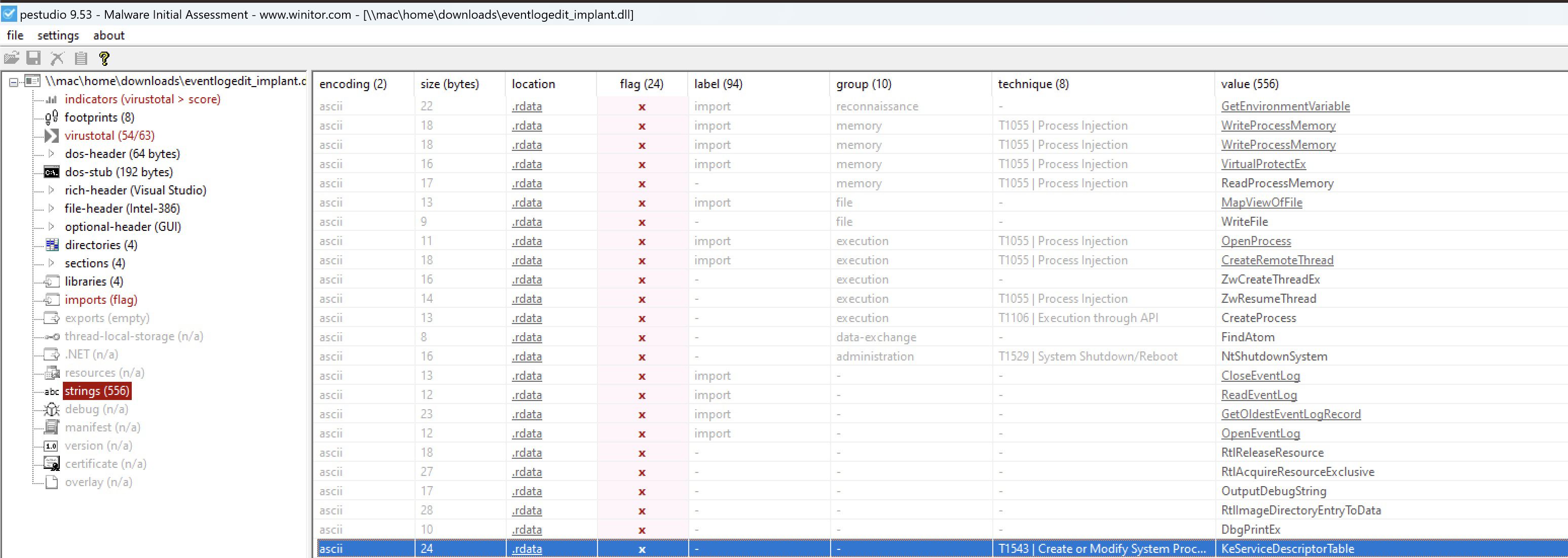

EQUATIONDRUG is one of the first tools that was developed in the Equation Group arsenal and one of the tools leaked through the Shadow Brokers. It is best described as a post exploitation platform that is loaded onto interesting targets following an initial infection by DOUBLEFANTASY. It was developed, possibly, as far back as 1996. It primarily targeted XP operating systems and GRAYFISH evolved from there to target additional Windows versions. Due to the extensive leaks of certain tools, anyone can examine some of these in Ghidra and PEStudio and gather some fascinating insights on their modus operandi. For example, at the bottom of the picture you can see KeServiceDescriptorTable is imported.

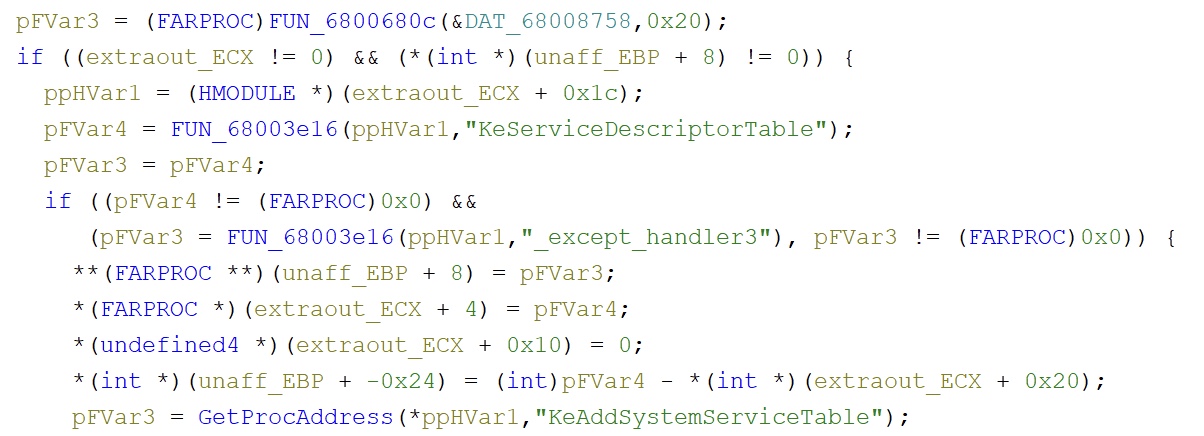

Perusing the decompiled source, you can find how this function was utilized.

I’ll be upfront that I’m not an expert in analyzing the decompiled and optimized code Ghidra returns from compiled sources, but we can see two clear calls here and correlate them with compiled information from Kaspersky. That is KeServiceDescriptorTable and KeAddSystemServiceTable. The latter of these is for adding new system calls to the SSDT which PeStudio actually missed when pulling strings out. On Vista and above this is no longer possible because there is only room for two; the kernels and win32ks. Equation Group was using these calls in order to add a new subsystem for a harder to detect angle of attack. To a modern audience, this is nothing new. Attackers have been leveraging Windows subsystem for Linux since it came out of testing. But at the time, this was quite novel since it was not a clearly documented Nt function.

Going back to Kasperskys research, they identified a key feature in FANNY (discussed here later) was that it was able to replace SSDT entries for functions with their own calls to perform whatever actions they want.

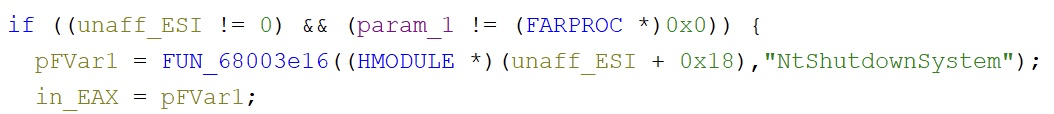

The implementation of the exploit in Fanny is more complex than in Stuxnet: instead of running just one payload the authors created a framework to run as many payloads as they want by replacing a system service call dispatcher nt!NtShutdownSystem with their own custom pointer from the user-space as shown in the next figure.

It’s not out of the question that a similar functionality was implemented into EQUATIONDRUG based on the below excerpt from an analyzed DLL.

We can breakdown the above sample in more manageable chunks. FUN_68003e16 is a function that takes an HMODULE and a char. An HMODULE is the DLLs base address. Looking at the compiled Assembly, the full instruction at this address is LEA EDI,[ESI + 0x18]. LEA is interesting because it does memory calculations to determine an offset and then store it in any register. I want to avoid diving into the weeds of this too much since it will be so easy to get lost in the nuance of what makes LEA special but basically it’s the only Assembly instruction that lets you perform memory addressing calculations without addressing the memory. This is significant because in FUN_68003e16, they call GetProcAddress for this offset and proceed to use the pointer declared to overwrite it from one instruction to another - just as was observed with FANNY.

EQUATIONDRUG also had a very unique capability at the time, and that was running before system startup fully completed. This methodology was more realized in the subsequent platform GRAYFISH. This predates EDR running before system startup and takes advantage of there being limited, if any at all, telemetry on what software and drivers are running at this time. The new book Evading EDR, by Matt Hand, has a section on how EDR runs pre boot actions. Chapter 11 Early Launch Antimalware Drivers.

Microsoft introduced a new anti- malware feature in Windows 8 that allows certain special drivers to load before all other boot-start drivers. Today, nearly all EDR vendors leverage this capability, called Early Launch Antimalware (ELAM), in some way, as it offers the ability to affect the system extremely early in the boot process. It also provides access to specific types of system telemetry not available to other components.

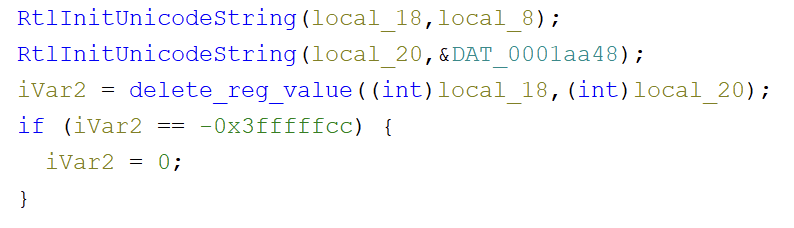

Thanks to the Shadow Brokers, we can get a good idea of some of the modules that were loaded as part of the framework. An interesting example is mstcp32.sys. This is for intercepting packets and executing commands based on fields seen. Though it’s for intercepting packets, it acts as a root kit, performing kernel calls on the fly to the registry and staying away from prying eyes. This can be observed in the below in some brief example calls to the registry.

DOUBLEFANTASY

DOUBLEFANTASY is one of the earliest droppers that Equation Group developed and it was discovered, interestingly enough, on CD’s sent to conference attendees that were at a Houston event. It was deployed as a generic dropper alongside a custom developed AutoRun file that loaded and executed the DLL from disk. Both it and the DLL employed a set of 0days to get root access which leads to the conclusion that they probably were meant to run independently of one another. When ran, a simple XOR decryption was performed and DOUBLEFANTASY checked the registry for installed AV from a pre defined list of vendors. At the time, the method of using key enumeration was “non alarming” as opposed to directly accessing the key. Nowadays we refer to this method as T1012 and there’s many detection patterns built around it. If no known AV was found, the malware persisted and executed further. Otherwise, it cleaned up and no one was the wiser. This was a lot simpler when there was such few AV vendors, and barely any of them were worth their salt at detecting threats. Nowadays, this is far less likely to accurately find AV to avoid and the key enumeration would raise alarms.

FANNY

The earliest sample Kaspersky was able to analyze had a compiled time stamp of 2008, two years before the same zero days would be used in Stuxnet, in conjunction with two more, to cripple Irans nuclear efforts. FANNY, due to the nature of the sensitivity of its payload, would naturally want to remain undetected by prying eyes. This means that targeting appropriate systems and individuals is of the utmost importance.

FANNY itself is easiest to think of as a persistent loader. Similar to Stuxnet, it uses the LNK exploit to autorun from USB drives even if autorun is disabled. Where they differ is that FANNY had a much broader target OS scope. Once FANNY executes, it fetches a payload from the C2 for further post-exploitation features. But it also has the ability to persist on the USB in order to relay commands back and forth from air gapped machines. This leads us into the first evasion technique that FANNY employs. Each time there is a successful infection, a counter decreases and when that hits 1, execution stops and FANNY stops further infections. This limits the spread and allows the operators to try and keep it contained within the target environment.

The next evasion technique is a little counter-intuitive. How might you weed out systems that have AV or other software that can expose your operation? FANNY did this by making it quickly obvious to AV and analysts that it was typical crimeware that should be removed. Any analyst looking at it would just write it off as malware that was cleaned up, maybe reimage the system to be safe, and Equation Group would keep their real tools safe from further scrutiny. And this worked well, really well. For six years it was detected only as part of the zbot malware family until Kaspersky went hunting for the Equation Groups tools based on a library signature. If the module persisted past this point, only then would further payloads be fetched.

GRAYFISH

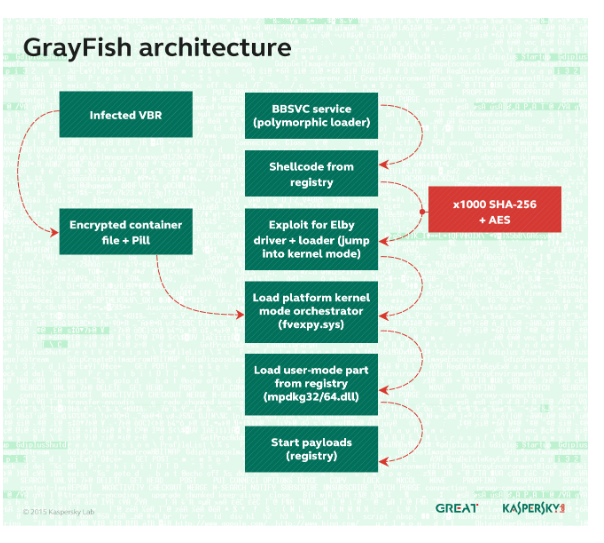

GRAYFISH is described by researchers as the Equation Groups most modern and sophisticated malware implant. This can be observed through numerous developments in methodology and tactics, such as leveraging 0days in HDD firmware to persist indefinitely after hard drive wipes , leveraging the registry to store and hide modules, and installing a bootkit to entirely control the start to finish boot process how they like.

When the computer starts, GRAYFISH hijacks the OS loading mechanisms by injecting its code into the boot record. This allows it to control the launching of Windows at each stage. In fact, after infection, the computer is not run by itself more: it is GRAYFISH that runs it step by step, making the necessary changes on the fly.

Normally, user space apps are not allowed to execute with ring 0 privileges. GRAYFISH bypassed this by leveraging a vulnerable driver, a technique now known as bring your own vulnerable driver (BYOVD.) This allowed the actors to execute their tools as the highest privilege available.

To bypass modern OS security mechanisms that block the execution of untrusted code in kernel mode, GRAYFISH exploits several legitimate drivers, including one from the CloneCD program. This driver ( ElbyCDIO.sys) contains a vulnerability which GRAYFISH exploits to achieve kernel-level code execution. Despite the fact that the vulnerability was discovered in 2009, the digital signature has not yet been revoked.

Another uncommon technique, for the time, was to live off of the registry. You can see this technique in MITRE ATT&CK as T1112.

The GRAYFISH implementation appears to have been designed to make it invisible to antivirus products. When used together with the bootkit, all the modules as well as the stolen data are stored in encrypted form in the registry and dynamically decrypted and executed. There are no malicious executable modules at all on the filesystem of an infected system.

Unfortunately, I can’t get any samples of GRAYFISH to look at further myself, so my summary of evasion techniques is limited to what’s publicly already been discussed, and there’s little available in that regard.

What’s Happening Today

That’s a historical look at evasion using Equation Group as an example, but evasion continues to change every day to adapt to new and changing EDR products. Below I have a set of some of my favorite techniques that I think represent a rapid growth in the offsec research environment. I can’t do each of them justice, they all deserve a post dedicated solely to them, but I will try to accurately summarize them for quick reference and provide a project that utilizes them.

Syswhispers

SysWhispers allows teams to directly reference syscall numbers without having to go through NTDLL for them. Hells Gate is an evolution of this and enumerates the NTDLL table for these numbers. SysWhispers is a header library/asm file combo that you can import into your project that has the correct ID for each call needed. Since you now have the correct ID numbers, you don’t need to import NTDLL to perform your syscalls. There’s been a few evolutions from the original SysWhispers, we now have 2 and 3. Each iteration has added different support and uses different compilers.

Sleep obfuscation

MDSecs Peter Winter-Smith can be credited with a lot of the work that went into developing sleep obfuscation, though back in 2016 Gargoyle laid much of the ground work. The example that I will use for this is Cronos, which credits Ekko, which in turn credits Peter for their inspiration. At a base level the Cronos function RC4 encrypts the running process then changes its memory from RW to RX. But sleep obfuscation is a lot more complicated than just this. Rewinding back to 2016, when scanners originally caught onto Gargoyle marking sections as non executable, SleepyCrypt came along and performed a single byte XOR to encrypt the malicious section. Now scanners will quickly brute force this which caused researchers to look for new techniques. Foliage was the first to use encryption of the running process and leveraged a ROP chain to achieve execution after sleep. Ekko and Cronos followed suit, iterating on this with Ekko utilizing an RSP register to make the ROP chain much more stable. This is accomplished because the RSP register is your stack pointer. This article by TrustFoundry is very helpful for further understanding this.

Spoofing the thread call stack

This is a lot like sleep obfuscation but it has a slightly different end result. You will perform the necessary steps of loading the shellcode, acquire your function pointers, then hook the kernel32!Sleep method to point to our own version. We allocate the memory, copy the shellcode contents into it, and then call CreateThread to begin execution. As soon as the implant finishes its tasks and attempts to sleep, our custom sleep callback is invoked which will copy then overwrite the return address on the stack to 0 - meaning the code goes no where. Then the implant sleeps for the specified period and afterwards restores the copied return address to the stack allowing execution to continue.

Reflective DLL loaders

Reflect DLL injection is a technique to run a DLL entirely in memory. First you calculate the size of the DLL to load, allocate a memory region for it, and copy it into there. But DLLs aren’t designed to run from memory, they’re designed to export functions while on disk. Stephen Fewers example solves this by exporting a primary function that handles this loading through a version of LoadLibrary that can handle being passed memory regions to read from. I’m not doing this justice with my explanation so I encourage anyone unfamiliar with this to play around with the exampel and attempt to get it to execute.

Disabling ETW

ETW stands for event tracing for Windows and provides robust heuristics on running processes and syscalls. This makes it a great tool for EDR to easily monitor processes for suspicious actions. EDR especially likes this because even if their hooks are removed from NTDLL to mask calls that way, the access is still logged through ETW. Bypassing both then becomes a requirement for engagements. Another MDSec researcher (I’m seeing a trend here…) Adam Chester, has a blog post as well that is linked from within the White Knight Labs article. He simply overwrites the start of the function with the return bytes so that when it is called it just runs its clean up routine and exits.

Removing hooks from NTDLL

This is definitely the simplest approach to evasion and entails removing EDR hooks placed in loaded copies of NTDLL. When a new process is started, that process needs to determine different syscalls to use. Those memory locations are referenced from NTDLL. EDR knows this and patches the copy loaded so that suspicious calls JMP to the EDR for analysis before returning back to normal process flow if it is determined to be safe.

There are a couple of ways to remove these hooks. You can remove on a per call basis so that maybe only CreateRemoteThread will avoid the EDR. Or you can copy the entire .text section of the file and overwrite how it is in the running process. I’ve not linked a project here because there’s a ton of different methods for doing it, all with their own ups and downs.